Sea Turtle Conservation and its Local Protagonists

Playa Los Negros beach, near the community of Isla Montecristo, is an important nesting spot for sea turtles and is home to a community-run hatchery.

It’s a cloud-covered night, and we’re walking briskly along Playa Los Negros, a beach that, apart from washed up driftwood and litter from the nearby mouth of the Lempa River, is practically untouched. Gio occasionally flicks on his flashlight to illuminate the way or scan the waves; most of the time, though, we walk in the dark. Our goal: to see a nesting sea turtle.

“One moment there’ll be nothing there, and the next you see a black mass coming out of the water,” Gio explains when we first start out. “Keep your eyes open.” Gio is what everyone calls Oscar Giovanny Diaz, an energetic young leader from the community of Isla Montecristo. He manages the turtle hatchery on Playa Los Negros and has been patrolling the beach alongside tortugueros (egg collectors) involved in the program almost every night this nesting season. He tells us that lately, they’ve had up to 20 Olive Ridley turtles nest on this five-kilometer stretch of beach each night.

Oscar Giovanny Díaz, who coordinates the turtle conservation project on Playa Los Negros, shows us how the hatchery works.

September, October, and November represent the high season for nesting Olive Ridley turtles in El Salvador. Four of the world’s seven sea turtle species – Green, Olive Ridley, Leatherback, and Hawksbill – lay their eggs on the country’s beaches. All four are, to varying degrees, threatened species by the IUCN’s classification. The odds are certainly stacked against turtles: it is an oft-cited statistic that of every thousand turtles eggs, only one will reach adulthood.

In this small Central American country one of the greatest threats to sea turtles is the consumption of turtle eggs as a delicacy. While the Ministry of Environment (MARN) made it illegal to consume and commercialize eggs and other marine turtle products in 2009, the law does little to deter, much less offer alternatives to, tortugueros for whom egg collecting has historically been an important source of income. That’s why community-run turtle hatcheries like the one on Playa Los Negros are so important. They work with egg collectors and coastal communities to make sure that turtle eggs don’t go to the black market, and instead become thriving, reproducing sea turtles.

Earlier in the evening, Bonerges Lovo, the hatchery’s keeper, showed us how it all works. It’s simple setup: a grid of black nylon string crisscrosses a large rectangular patch of sand that’s separated from the rest of the beach by a shallow ditch and a fence. Dried palm fronds provide shade and help regulate the temperature of the sand. Each square of the grid contains a nest and is marked with a tag indicating the collection date and number of eggs in the nest. As nests get closer to their due date, they’re enclosed in a cylinder of mesh wire so that hatchlings can be easily collected and counted before they’re released to the ocean.

Teams of tortugueros patrol the beach in shifts, and when an egg collector finds a nest, he immediately brings the eggs back to the hatchery where they’re counted, reburied, and marked. Egg collectors are paid $1.25 per fourteen eggs (a dozen plus two eggs which they contribute) and another $1.25 are put aside to purchase items – boats, nets, and other fishing materials, for example – in order to support alternative livelihoods for egg collectors and diminish their reliance on turtle eggs. The project is funded by FIAES and Izote and coordinated by our partners at the Mangrove Association.

It’s an innovative – and more importantly, effective – model for turtle conservation. The hatchery at Playa Los Negros has been functioning for eight years now, and each year the number of nests collected and hatchlings released steadily increases. In 2013, they collected 53,674 eggs from 582 nests and released 47,980 live hatchlings. When we visited in mid-October of this year, the hatchery already had well over 650 nests.

Students show off their turtle knowledge and costumes at the 2014 Hawksbill Festival on Isla San Sebastián.

Conservation efforts are complemented by ongoing educational campaigns in coastal communities. ICAPO, the Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative, is another of our partners in the Bay of Jiquilisco. In addition to running hatcheries to protect the critically endangered Eastern Pacific Hawksbill sea turtle, ICAPO organizes the annual Hawksbill Festival. The festival is a celebration of conservation successes and an incredible opportunity to raise awareness among surrounding communities, especially young people, about the difficulties turtles face. This year the festival was held on the grounds of the school of La Pirraya, on Isla San Sebastián, and hundreds of adults and kids enjoyed the festivities: a parade, marching bands, speeches, a puppet show, clowns, turtle costume contests, games, and a soccer tournament – all dedicated to sea turtles and what we can do to mitigate our impact on them.

After an hour roaming the beach at Playa Los Negros, we get a sign: a tortuguero in the distance is waving his flashlight in the air to signal that he’s found a nesting turtle. We run to the spot and as we arrive, breathless, we spot her: a female Olive Ridley a little smaller than a car tire that has just laid a nest of several dozen eggs. She’s returning to the ocean; moving through the sand is a visibly laborious process. Eventually she disappears into the waves again.

Having achieved what we set out for, we head in for the night. I’m glad to have been a part of, if only for a few hours, this incredible process and to have caught a glimpse of the beauty and resilience of nature. The tortugueros will be patrolling the beach until dawn, continuing the important work of protecting these vulnerable species and restoring the environment.

Students from the communities of Isla Montecristo and La Pita help release hatchlings on Playa Los Negros Thursday, November 6, 2014.

Planting Financially Sustainable Seeds in the Lower Lempa

MBA students from the Monterey Institute of International Studies after presenting their final business plan

The team of MBA students arrived on a Tuesday, tired from their overnight flight, but enthused by the energy of being in El Salvador. For our MBA capstone project at the Monterey Institute of International Studies (MIIS), we had been working on a business plan for a newly formed agricultural cooperative, Xinachtli, based in rural El Salvador. The team was beyond ready to meet the founders of Xinachtli- the Mangrove Association and La Coordinadora– and grasp the aha understanding that transpires from being on the ground.

Students from MIIS have worked closely with the Mangrove Association and La Coordinadora for nearly 10 years through the Team El Salvador (TES) January-term program. One of TES’s primary projects has been to evaluate the numerous services that the Mangrove Association has provided to small-scale farmers and fisherfolk in the region. To improve the financial sustainability of these services and support further economic opportunities in the region, the Mangrove Association has decided to create a separate for-profit cooperative, Xinachtli. The team of MBA students worked this past summer with the founding members of Xinachtli to develop a business plan that would enable the cooperative to support its social mission and assume financially sustainable operations.

We made a couple stops on the way back from the airport- everyone had their first taste of the famous Salvadoran pupusa and Salvadoran Spanish- before throwing them into the life and work of the Lower Lempa. The team’s first meetings with the Mangrove Association and Xinachtli were set for the next morning. We prepared for the meetings as the team adjusted to their new home- set-up the fans and tested the hammocks, checked out the latrines and glimpsed the organic community garden. I showed them the fridge to keep our stock of chocolate from melting and we worked late into the evening.

This past summer marked my fourth visit to the Lower Lempa. I’d been a team leader of TES projects for the past two years and spent my prior summer continuing work from January. During my previous time in the Lower Lempa, I worked with the Mangrove Association to strengthen its community plan for local management of natural resources and develop a network for community-based ecotourism. As they say here, I had drunk the water from the Lempa River: I was hooked. The Mangrove Association’s dedication to fight for community empowerment, environmental sustainability, social justice and intelligent policies to promote economic security compelled me to return: to learn from their expertise and experience and to apply the skills and knowledge I was learning in graduate school.

“Mejorar la calidad de vida para las familias,” or improve the quality of life for families, the founding members of Xinachtli nodded in agreement as they discussed the social mission of the cooperative. The entire MIIS-MBA team was on the ground for about two weeks in total; I was based in the Lower Lempa for the summer. We ultimately created a business plan that we felt would best enable Xinachtli to secure the sustainability of its mission and business operations. However, Xinachtli will operate in a dynamic environment, of which the team only glimpsed a small part and in which local knowledge and experience will be critical in shaping a viable business plan. Accordingly, the fun part still lies ahead: working alongside the Mangrove Association and Xinachtli to assess the proposed business model and adopt the plan that best suits the conditions under which Xinachtli will grow. I look forward to the coming months as an exciting and fruitful time in which Xinachtli will continue to work with business professionals, experts in cooperative governance and local smallholders to conceive a business model that supports socially and environmentally conscious economic opportunities in the Lower Lempa region.

Congresswoman Estela Hernandez to Speak at Bioneers

This weekend, El Salvadoran Congresswoman Estela Hernandez will be in the Bay Area to present at the Bioneers Conference. Estela is a community organizer and a key leader of La Coordinadora, and its affiliated NGO, the Mangrove Association. She was elected to the Salvadoran National Legislature in 2012. She now sits on the Environment and Climate Change Commission in the Legislature, the committee that writes environmental legislation at the national level.

On a panel called “Building Power From the Rubble: How Frontline Communities are Creating Resilience to Climate Disasters,” Hernandez will discuss her work with La Coordinadora, which has led the way the last 15 years in disasters response. Community-based disaster preparedness committees, climate-adapted diversified agriculture, community-protected coastal forests, ecosystem restoration, ongoing youth engagement and leadership development are stepping stones towards a more resilient future. La Coordinadora’s strong grassroots movement for democracy has brought their leadership into political power and allow for many of their innovations to become national policy.

Film maker Avi Lewis will join Estela Hernandez and EcoViva Executive Director Karolo Aparicio on the panel. Lewis has documented the successes of La Coordinadora along with other efforts worldwide for his upcoming film “This Changes Everything,” which complements Naomi Klein’s book of the same title.

In addition to Bioneers, EcoViva and Estela will be meeting with local foundations, supporters, and political leaders. We look forward to welcoming Estela to the Bay Area.

Live in the Bay Area and want to be involved in Estela’s visit?

- Join us at Bioneers using discount code ECOVIVAB14

- Listen in to Poder Latino (Radio 1010 & 900 AM, based in El Cerrito, CA) on Friday at 1pm for an interview with Estela

- Attend Naomi Klein’s book lecture and book signing for her new book, This Changes Everything, co-sponsored by EcoViva. It is this Friday, October 17 at the Veterans’ Building in Santa Rosa, CA. Purchase tickets for $10 here.

Communities and Authorities to Dialogue on New Coastal Investments

**For English Subtitles, click on the Closed Caption (CC) button at the bottom right corner**

This morning, the government of El Salvador and the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a U.S. foreign aid agency, signed a 5-year development and investment package worth a total of $365 million- $277 of which is provided by the MCC, $88.2 by the Salvadoran government. Made up primarily of U.S. taxpayer money, this investment is destined to improve coastal highways and key border crossings, increase opportunities for schooling, and help attract new private investment through regulatory reform and targeted public investment.

Historically, El Salvador’s coastal zone has long been neglected by proper public policy to drive sustainable rural growth. As such, these new investments overseen by both the U.S. and Salvadoran government will require the participation of a strong, active civil society to ensure that development enhances coastal and rural areas, and contributes to an inclusive approach to economic growth.

Over 100 organized communities in La Coordinadora del Bajo Lempa y Bahia de Jiquilisco, and La Coordinadora del Puerto Parada, have been preparing for these new coastal investments by presenting their model of rural development to government officials, and highlighting the importance of viable coastal ecosystems as the greatest driver for sustainable growth. With the help of EcoViva, local community and municipal leadership have also been learning about the upcoming MCC initiative, and communicating directly to decision makers in San Salvador and Washington about the need to put local environmental and social processes in the Bay of Jiquilisco front and center.

New, unprecedented investments in coastal El Salvador present new opportunities, but also new challenges. These challenges cannot be met without the active participation of an informed civil society. To date, our partnership has created a basis for dialogue and accountability between communities and authorities that will be crucial in the coming months, as studies are completed and aid programs along the coast begin to be implemented in 2015. This has been accomplished through the following:

- Congressional briefings in Washington and meetings with MCC decision makers to learn about the scope and scale of new investments, alongside corresponding policy reforms, and explain challenges with El Salvador’s current environmental and social policies.

- Outreach and informational meetings with local leadership and national authorities, to discuss the significance of MCC foreign aid within current local development processes.

- Oversight and analysis of policy reforms in El Salvador [MCC, Public-Private Partnerships, & seed] that inform a local coastal coalition about their potential to impact rural areas like the Bay of Jiquilisco.

- Outreach to the conservation biologist and sea turtle community, together with the Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative and VIVAzul, to collect over 7,000 signatures to protect key Hawksbill habitat in the Bay of Jiquilisco from unchecked development.

- Formalize alliances with an array of specialists and institutions to improve coastal management

In following and informing local leadership, EcoViva and the communities of La Coordinadora have already realized the following outcomes for the benefit of El Salvador’s coastal areas and communities:

- Acknowledgement on the floor of the U.S. Senate of the importance of including local communities in consultation and project design.

- A formal study of the Bay of Jiquilisco’s biodiversity, and carrying capacity, to be conducted by the MCC and government of El Salvador prior to any new investments along the coast.

- A commitment from the MCC to protect critical Hawksbill nesting habitat along beaches and mangrove forests.

- Headlining a November 2013 national conference on mangrove conservation, governance, and the evolving regulatory framework.

- Advocating on behalf of El Salvador’s domestic seed breeding sector to successfully pressure the United States to de-couple free trade concerns on seed procurement from aid conditions.

- Spearheading cooperation agreements directly with the Minister of the Environment and leadership at the University of El Salvador to forward coastal conservation and governance structures—led by community leadership at La Coordinadora.

Moving forward, EcoViva and community leaders will continue strengthening their ongoing work in coastal ecosystem and water management that is already acknowledged by the MCC and Salvadoran authorities as a model for the region. This will allow communities to propose effective alternatives to coastal management that are not only considered during upcoming public consultation, but also applied as real oversight and compliance over new public and private ventures along the coast.

Local Youth Groups Form to Address Community Needs

Three members of the San Marcos Local Youth Group working on their reforestation initiative in the local communities

There’s a new movement afoot in the Lower Lempa: Grupos Locales de Juventud, or Local Youth Groups.

Mirrored after La Coordinadora del Bajo Lempa’s decentralized and democratic model of social organization, each Local Youth Group gathers young women and men from surrounding communities to discuss issues affecting them and plan concrete actions to address these issues.

There are currently five active Local Youth Groups in the area; approximately 75 youth from 41 communities participate. They are supported by the Mangrove Association’s youth program promoters, who facilitate meetings and connect the youth with resources for their projects. Just in the last month, the groups have planted trees in community areas, planned fundraising raffles, and held movie screenings for kids. Through these activities, young people learn how to work together to make local change, engage with their neighbors and their environment, and build positive spaces for peer support.

Not only do the groups provide a safe space for Salvadoran youth to be involved in positive activities and community development processes, but they are shaping the next generation of community leaders. Indeed, many of the Mangrove Association’s staff are a product of past youth program initiatives. Local Youth Groups will ensure the continuity of strong community organization and development in the Lower Lempa.

As the youth spent the summer organizing into Local Youth Groups, we wrapped up our 4th Annual Viva Fund campaign, supporting youth empowerment in the Lower Lempa. With your help, we raised a total of $7,500 to support youth initiatives, including the Local Youth Groups. Thank you for raising money, donating, and spreading the word!

Welcoming New Team Members

Earlier this summer, we had the pleasure of welcoming Jeanne Muller and Amy Kessler, two new team members based in El Salvador. We’ve worked with both of them before as interns, researchers, and Community Empowerment Tour participants and are happy to have them on board. Join us in welcoming them to our team!

Jeanne Muller, International Program Associate

Jeanne Muller with Chema Argueta of the Mangrove Association and Aaron Voit, former Field Coordinator

Jeanne moved to El Salvador in May of 2014 following seven months interning in our office in Oakland. As International Program Associate, she works to support our communications strategy by writing content for the blog, taking pictures, and keeping us informed about projects on the ground. She also is a facilitator and guide for our Community Empowerment Tours and works with the Mangrove Association’s youth program to strengthen its projects, among other things. When she’s not working, she can usually be found gorging on panes dulces and being silly with her host mother and sisters.

Jeanne earned her undergraduate degree in Latin American Studies with a minor in Spanish from Dickinson College in 2013. She has lived and worked in Paraguay and Ecuador but it is her first time exploring Central America. More than anything, Jeanne is thrilled to be learning firsthand what democratic, sustainable, community-led development looks like in practice. Find blogs from Jeanne here.

Amy Kessler, Field Coordinator

Amy has spent the last two years working part-time with EcoViva and the Mangrove Association while finishing her studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. Upon graduating with a dual Masters in International Environmental Policy and Business Administration, she became a fulltime member of the EcoViva team as the Salvadoran-based Field Coordinator. She has been working with the communities in the Lower Lempa to strengthen their efforts in local management of natural resources and to promote sustainable income opportunities. She will continue to provide technical support and policy advocacy, and is particularly interested in applying economic and business principles to create forward thinking solutions for the environmental and social injustices in the Lower Lempa.

Amy first gained an appreciation for the interrelations of natural resource use, environmental sustainability and economic development during her undergraduate years when she studied marine biology in a small fisherman town of Mexico. After graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in Biology and Environmental Studies from Kenyon College, she then lived abroad for several years before returning to the States to pursue further studies. Find blogs from Amy here and here

Is the U.S. Sowing the Seeds for Child Immigration?

While tens of thousands of Central American children stream across our Southern Border, the U.S. government scrutinizes a rural development program proven to create real jobs and opportunity in communities of origin and for hundreds of poor Salvadoran families.

Salvadoran farming communities celebrated a victory for food security and sovereignty this month. After posturing by the United States on how El Salvador purchases corn and bean seed to feed over 560,000 low-income subsistence farmers and their communities, U.S. officials backed off of the issue. The Salvadoran government proposal on seed had satisfied their demands, the U.S. Embassy said, and it would no longer hold up a much-anticipated $277 million aid package over whether or not El Salvador offered its procurement to transnational agricultural suppliers.

This was no small feat, considering current behavior of the United States in its dealings with El Salvador. For the past nine months, the United States has been conditioning a new round of development aid through the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) on specific reforms to a variety of Salvadoran economic and security policies. Since 2011, the Salvadoran government has delivered on a number of policy reforms, including new frameworks to promote public private partnerships. Throughout this process, the United States has not acknowledged progress in any of these reforms unless specific laws were passed, signed and ratified in El Salvador.

But on corn and bean seed, the United States conceded that it would table the issue until the fourth quarter of 2014, substantially softening its position with El Salvador for the first time in months.

The U.S. softening on seed reflected a stark political reality evolving in Washington: the United States was beginning to look tone deaf in Central America. As you read this, tens of thousands of children are streaming across our southern border, many of whom are fleeing violent situations that persist in impoverished local communities in places like El Salvador. How could the United States make overtures toward improved cooperation in the region on one hand, while on the other obstruct rural development programs proven to create real jobs and stability for thousands in the family farming sector?

Far worse, the United States appeared to be holding up a development aid package designed to generate much-needed economic growth over a relatively modest rural food security program. As actors like EcoViva have demonstrated, the U.S. was doing so based on scant evidence to back up their position. Seed was also beginning to overshadow more important priorities like a new money laundering law. Heightened pressure from the press, as well as Democrats in the House of Representatives, also elevated the issue to a place that neither Washington nor the U.S. Embassy wanted it to be.

What transpired on seed reveals a deeper issue concerning inconsistencies with U.S. policy in the region, and Washington´s acknowledgement of the reality of the public programs that improve the lives of the majority of Salvadorans—either with those children that flee violence in their home communities, or those that stay behind to eek out a living.

As EcoViva has reported in a number of news outlets (here, here, here, and here), on this blog, and directly to U.S. officials, the Salvadoran government has made measurable progress in improving the way it purchases corn and bean seed over the last five years. In 2012, the Ministry of Agriculture opened up its procurement to purchase better, more desired corn seed at a significantly cheaper price than what had been offered historically to El Salvador by transnational companies like Monsanto and Pioneer. Through an executive decree, the government was able to procure a product that it wanted, a variety of certified hybrid corn seed known as “H59”, from 16 domestic entities—many of whom are local cooperatives consisting of the very same limited-resource family farmers that qualify for support through El Salvador’s Family Agriculture Program.

This decree also allowed the government to respond in a timely manner to seasonal requirements of their family farmers that produce corn–requirements that don’t conform to the existing bureaucracies and timelines for contracting. How can El Salvador fulfill its contractual obligations to pay seed producers to plant product in December or January, if it is obligated by law to wait until January to begin a three-month bidding process before any seed can go in the ground? Over 400,000 family farmers plant corn in May each year to correspond to the wet season, and can’t wait around for a bureaucracy to put corn in the ground, or food on their table.

All this didn’t matter, said the United States Trade Representative (USTR) in Washington. Above all, El Salvador needed to produce an “open, competitive, transparent, and rules-based” procurement process to purchase seed. Essentially, the U.S. government was under the impression that El Salvador’s seed buying process was systematically excluding certain kinds of businesses—in this case, transnational seed providers. When word got out that the U.S. was conditioning aid on El Salvador’s purchase of corn and bean seed from transnationals like Monsanto, the “anti-Monsanto”and “anti-GMO” drums inevitably began to beat on the internet and social media.

But as EcoViva reported, the actual buying process in question during 2014 had already opened up to international businesses since 2012. Requests for bids had been published openly in domestic newspapers, and the same direct purchasing methods under scrutiny for seed had taken place numerous times in the past while USTR remained silent. EcoViva and collaborators at OxFam America provided documentation and existing regulations to USTR related to the bidding process and oversight on seed , which USTR admitted they had never seen before. Moreover, seed procurement prior to 2012 also appeared less competitive: just five businesses provided seed at nearly twice the price, versus 18 currently at more affordable prices for the government.

In other words, the current procurement produced more accepted bids for a better product at a cheaper price, and information was accessible to EcoViva and other growers who applied for the bid from the Ministry of Agriculture. It even included several businesses that had imported seed, and participated in past procurements that USTR had no problem with, and allowed the government to obtain a product through a bidding process that allowed its budget to reach a historic number of farmers, each of whom receive 22 pounds of H59 and corresponding farming inputs. How was this process not competitive, open, transparent, or rules-based? And, more importantly, how did it represent a “regression” in procurement policy, as had consistenly been the USTR´s claim?

Now, it’s no surprise that those who failed to compete for the current seed procurement contracts got upset and called foul. Last April, a representative from the American Chamber of Commerce complained in a Salvadoran newspaper that the seed provided by businesses like Monsanto affiliate “Cristiani Burkard” was a superior product that should be purchased over domestic, certified corn seed like H59. Not so fast, said officials at the Salvadoran Ministry of Agriculture. Monsanto varieties like 30F-Decal and H5, they say, provide a lower grade corn by-product suitable only for tamales, exhibit lower germination rates, and have demonstrated reduced yields on Salvadoran farms compared to H59. According to El Salvador’s National Seed Law, amended most recently in 2005, the Ministry of Agriculture is obliged to purchase adapted hybrids with 80% germination rates, accompanied by field tested adaptation studies from at least 10 discrete samples. H59 met these requirements, 30F and H5 from Monsanto did not. Not to mention that these businesses were offering the 30F and H5 varieties for higher prices than the domestic cooperatives producing H59–$156 a unit versus $125 by domestic producers of H59. Currently, H59 is only grown in El Salvador by Salvadoran farming cooperatives like the five in the Lower Lempa, making it uniquely adapted to the region and growing conditions.

Of course, all policies and processes can be improved. Nearly three weeks after the Salvadoran government offered a proposal, the U.S. Embassy finally acknowledged publicly that they were satisfied with how things would progress—and only after press coverage associated with the region and child migration flows began to look untenable. USTR commented that it was willing to work with El Salvador on specific improvements to the seed procurement method, including the timing, publication, time to present offers, and open access to information for the bids among all interested parties.

By all means, let’s improve paperwork transparency and expand access to information. The corn and bean seed procurements should also be made available on El Salvador’s government contracting website, “COMPRASAL.” But again, these same issues signaled by USTR on seed procurement also occur repeatedly in other procurements throughout the Salvadoran government—procurements that conform to Salvadoran law, but could present problems under the same CAFTA-DR Chapter 9 issues being brought to bear by USTR on seed—if USTR decided to enforce them, like they decided to on seed. And it seems difficult to justify how publicizing a call for bids for 40 days versus 15 significantly improves “openness”, when the procurement is repeatedly made every year, and product standards for seed are established in a 2005 law accessible to anyone with a Google search engine.

Making government purchasing more transparent is an important goal. But does it justify an unprecedented hold up in foreign aid to a country that has proved its commitment to work closely with U.S. actors like the Millennium Challenge Corporation? As press heated up over seed procurement, U.S. officials decided that their arguments on seed no longer warranted the potentially bad publicity at a time when Congress was scrutinizing the Obama administration’s actions and policies in Central America on immigration, security and development—and well they should. So far, Obama´s $3.7 billion dollar request contains $300 million for State Department actions geared toward improving the Salvadoran condition. Perhaps the United States should first clear up how its current programs contribute to addressing migration “push factors” in the region.

Salvadoran seed producers should also remain confident but vigilant. They currently provide a product that the Salvadoran government prefers at a competitive price. If the U.S. is serious about improving transparency and competitiveness of this bid, this should only be made more apparent in the months to come.

UPDATE: El Salvador’s “Action Plan”

After this blog was published, the U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador, Mari Carmen Aponte, clarified on a national television program that policy reforms such as seed purchasing, public-private partnerships, and a new money laundering law were suggested by the previous Salvadoran administration under Mauricio Funes, and included a total of 13 distinct policies to be revised to improve El Salvador´s investment climate. These policies were detailed in an “Action Plan” proposed by El Salvador, she said, and since the approval of $277 million through the Millennium Challenge Corporation, the United States was seeking timely completion of these efforts.

Like any country on Earth, El Salvador has a responsibility to meet its obligations under international and bilateral agreements, including dealings with the United States. Foreign aid should also not be a blank check. However, the exact nature of these obligations, including who from Washington is ultimately responsible for enforcing their completion, seems to exist on a constantly shifting and sliding scale. Regarding El Salvador´s “Action Plan”–the details of which have not been made public–EcoViva sees a lack of consistency within Washington development agencies on who ultimately oversees the reform process, and who has final say on progress and completion of this “Action Plan” in Washington.

For its part, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) has been forthcoming in its particular requirements for an improved investment and business climate in El Salvador. Until November of 2013, these policies had included bureaucratic improvements in business start-up and transaction costs, illegal property seizure, improvements in special business zones, reforms to police actions on financial crimes, and public private partnerships. Then, in December 2013, the MCC sent a letter to the Salvadoran government which stated that El Salvador would also need to account for free trade compliance issues, alongside specific improvements to public private partnerships and money laundering policies, both of which had recently been passed and approved by large margins in the National Assembly.

Where had free trade compliance come from? It had certainly not been mentioned previously by the MCC. Nor was it on the agenda of the Council for Economic Growth in El Salvador, a private sector round table that embodies the U.S. “Partnership for Growth” with El Salvador–or at least, as far as EcoViva could discern from conversations with U.S. officials and individual members of this round table, staffed by the IMF and members of FUSADES, a Salvadoran think tank.

To date, the Council for Economic Growth’s reform agenda for spurring private sector participation in the Salvadoran economy has not been made available to the public–despite the fact that calls for greater civil society participation and transparency in the Partnership for Growth had been acknowledged by the U.S. State Department.

As it turned out, the United States Trade Representative (USTR), the federal agency charged with promoting and enforcing free trade agreements around the world, like CAFTA-DR, had pressed the issue. USTR sits on the MCC’s Board of Directors, officials said, and had raised concerns about what they considered to be “regressions” in El Salvador’s compliance with CAFTA-DR standards. These regressions, they said, were outlined in a recent report that included polices on international property rights, pharmaceutical purchases, Points of Origin, and seed procurement. USTR’s seat on the MCC Board allowed them to not only comment on approving MCC aid to El Salvador–which was granted a green light by Board members, including USTR, in September 2013–but apparently USTR could also press for specific reforms, and re-prioritize them before the MCC and El Salvador could sign and ratify the $277 million aid package, as long as the reforms added to general improvements in El Salvador’s business and investment climate.

Ah ha, okay. So perhaps USTR could help us understand whether or not progress on El Salvador’s “Action Plan” was being made or not. But in conversations with USTR, it became clear that USTR didn’t consider themselves to be either empowered or capable of assessing progress on El Salvador’s action plan. As reported by EcoViva, USTR itself acknowledges that they can neither veto an MCC aid package as a Board member, nor define what specific progress looks like in advancing policy reforms. USTR as a federal agency has its own mechanisms for enforcing free trade compliance, just as the MCC utilizes its own evaluation process for assessing good governance and trade policies in partner countries like El Salvador.

So, the search for who has final say in Washington on progress toward El Salvador’s “Action Plan” continues. Unfortunately, it may take a flood of tens of thousands of Central American children to get a reply, and perhaps from the highest levels of the Obama administration as El Salvador’s president and other leaders meet in Washington with President Obama and Vice President Biden. It’s unfortunate that our border crisis may be the only thing to jolt Washington out of its tendency to play hot potato with its diplomatic mission on El Salvador and the region.

Ultimately, El Salvador and other Central American government have the greatest responsibility for tackling the immense security and economic challenges facing the region. But this display of U.S. diplomacy, and the uncertainty it has helped engender, is not helping.

Young Entrepreneurs Start Local Tilapia Business

“Oh, we forgot the fish food!” Maira laughed as she turned back the way we came. I had just met up with Maira Alvarado, 22, and Kevin Quinteros, 20, at the community center in Ciudad Romero that morning. They had graciously agreed to give me a tour of the tilapia farming business they’ve launched with two of their peers from the aquaculture program at Megatec, a technical university in the department of La Unión. UDP-ABL, Unión de Personas Acuicultores del Bajo Lempa, as the business is called, is one of two youth-led tilapia farming projects in the Lower Lempa. (The other is a few miles away in La Limonera and I was also able to meet its leadership Raúl Domínguez, 21, and Jenny Chávez, 22.) After picking up the food from Maira’s house – a pine green bucket filled with small sand-colored pellets – we set off again for the project site.

Thankfully it’s a short walk from the center to the tilapia farm because even though it’s only nine o’clock the day is already hot. Turning the corner after the new community health clinic, we arrive at a verdant lot. In front is a plot of newly planted corn and behind, in a grassy patch, sit two large cinder block tanks filled with dark glassy water that glints in the sun. I’m told that each contains 1,732 Oreochromis niloticus, commonly known as grey or Nile tilapia (one tank is also home to a freshwater turtle, we later observe). Though the fish spend the day at the bottom of the tanks where the water is cooler, I can see lots of little mouths gobbling up pellets as Kevin scatters them over the surface of the water.

“We feed the fish three times a day, at 9:00 am, noon, and 3:00 pm. Every two days we rotate who’s responsible for feeding them, and every eight days we change the water. We also regularly monitor the conditions of the tanks and the development of the fish,” Maira explains. The young entrepreneurs are recent graduates of Megatec, where they’ve been studying for the last two years, in large part thanks to scholarships provided by the Mangrove Association and EcoViva. Other than Kevin, who is from Usulután, all are from nearby communities – Ciudad Romero, El Carmen – and were very involved in the Mangrove Association’s youth programs as teenagers. In fact, it was based on their leadership skills and commitment to their communities that they were awarded scholarships to continue studying.

Last year, the group was granted seed money for the tilapia project after their business proposal won top marks in a competition organized by the Organization of Ibero-American States for Education, Science and Culture (OEI). They already had some land with a tank that had been built as part of a previous initiative seven years ago. The second tank was completed in January 2014, and in April they “planted” the first batch of tilapia fry, which take about three months to mature. It’s an exciting moment because, after more than a year of hard work, Maira and her associates will be harvesting and selling the largest of the fish this weekend.

Of course, the young entrepreneurs have encountered a number of challenges. While the OEI seed money bought materials to build two tanks, fish fry, and enough food for the first few growing cycles, the entrepreneurs and their families have had to cover transportation of materials and labor costs. The project site also lacks electricity, which is necessary to run the oxygenation system for the tanks; fish growth and production have suffered as a consequence. They are seeking financial support from the Mangrove Association for the funds necessary to electrify the plot. Yet despite these obstacles, the group is confident: “It’s been a difficult process, but I told myself that if I’ve already come this far, why would I leave it now? Sure, it’s just beginning and we’re going to have to work hard but something good will come of it. We have to keep moving forward,” Kevin told me.

Now that they are fully-formed aquaculture technicians, Maira, Kevin, Glenda, and Wilson hope to continue serving their communities not only by offering a high-quality product at a good price, but eventually by providing employment to other community members, particularly youth, as they expand their operations. Poverty, lack of employment, and gang violence push many young Salvadorans to emigrate, which is why these tilapia farming projects are so remarkable. “Here there are few opportunities for young people. We’ve been very lucky and also worked really hard to build this,” said Maira.

Through our conversation, it becomes clear that the opportunities that the Mangrove Association offers to young people in the Lower Lempa – from leadership programs to scholarships to, now, grants for small businesses – are crucial to strengthening communities both socially and economically. Thanks to these spaces, youth leaders like the entrepreneurs of UDP-ABL are contributing to the development of their communities.

Viva Fund Kick-off: Support Youth in El Salvador

Recently the media has been filled with stories of unaccompanied minors heading north from countries in Central America. Gang violence, economic insecurity, and a lack of opportunities are frequently cited as the reasons youth are pushed out of their countries of origin and in to the United States

How do you address these issues head on? How do you create more opportunities for education, creative expression, and economic security within El Salvador? While the solution is complication, the first steps to take are simple- let the youth take the lead.

Since 2002, EcoViva has supported youth programming in the Lower Lempa region of El Salvador. Overtime, the programs have changed to reflect the needs of local youth to include leadership training, capacity building, educational opportunities and extracurricular activities including art and sports.

To ensure the continuation of these programs and to strengthen the future generations in the Lower Lempa, we founded the Viva Fund Campaign in 2011 at our 15th anniversary celebration. Initially a scholarship fund, the Viva Fund has expanded along with our programs in El Salvador to include support for other initiatives. This year, youth have become entrepreneurs, putting their education and leadership training into practice by creating economic opportunities for themselves and other members of their community.

Today, we kick off our 4th annual Viva Fund Campaign. Please join us in celebrating the vibrant young leaders, taking control of their lives and investing in the future of their communities. Over the next six weeks, we will be sharing stories from the Youth Program and raising money to support their continued efforts. Donate today to ensure these efforts thrive.

Here are some ways to support the 2014 Viva Fund Campaign:

- Donate– Any amount helps. $15 can buy materials to support he artisan cooperative, $54 can pay for a field trip, and $80 can buy a bicycle.

- Become a Viva Fund Ambassador. Email me (Tricia) to join our team of crowdfunding ambassadors, spreading the word and fundraising to support the youth program

- Share the link to our donation page with your friends and family – through email, social media, or a short note.

- Host a house party or happy hour to tell your friends about why you support the Viva Fund

- Have other ideas? Email me to get started!

We thank you for your support and look forward to sharing more about the Youth Program in the weeks to come!

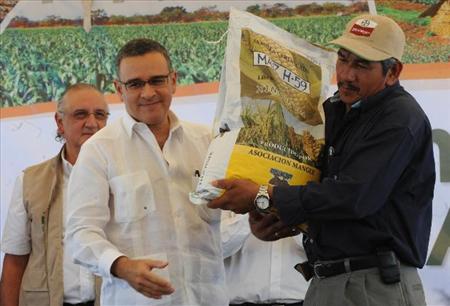

A member of the cooperative from the Lower Lempa presents former President Mauricio Funes with certified seed, as the Minister of Agriculture looks on

Seed distribution is the backbone for El Salvador’s Family Agriculture Program. It is heralded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as a model for rural development across the Central American region. Its seed distribution program responds to immediate food security needs of over 325,000 impoverished, small scale family farmers who would otherwise not have access to affordable farming inputs that helps them put food on their table, and feed their communities.

The Salvadoran government’s ability to respond in a timely way to seasonal and growing requirements is fundamental to the success of this program. Corn and bean crops do not conform to bureaucratic procedures or national budgeting timelines. Thanks to the particular producers who have currently supplied the kind of seed that the Salvadoran government desires, at the cheapest price, this distribution program surpassed its goals in 2013, and reached over 400,000 small scale farmers while contributing over $25 million to the rural economy that led to record corn yields nationwide.

Below is a response to the Embassy’s arguments on free trade compliance and seed procurement, published on the U.S. Embassy homepage on Thursday, June 19.

Embassy: “The U.S. government concern with the Ministry of Agriculture’s procurement program is completely unrelated to the purchase of genetically modified seeds. Any rumor to the contrary is false.”

EcoViva believes that recent civil society comments on U.S. support of Monsanto and GMOs reflect a general frustration with inconsistencies by the United States per seed procurement policy. Past procurement orders prior to 2012 clearly reflect a less competitive process that led to the acceptance of an inferior product at a higher price, from a fewer number of businesses. Through procurements prior to 2012, a Monsanto affiliate was awarded over 70% of the procurement order with more expensive seed product that offered yields achievable only with expensive chemical additives provided by the same company. Such expenses, when applied to the Government of El Salvador´s limited budget, made their outreach to the small scale farming sector less effective, in that they could not reach as many farmers that contribute to greater overall national yields. In contrast, current procurements have led to record yields and service to more farmers, thanks to a product especially adapted to El Salvador’s growing conditions.

If the United States is not providing preference to specific U.S. providers like Monsanto, it should clarify why it did not comment on procurement procedures prior to 2012, when these procedures clearly reflect difficulties in the same criteria of “openness, transparency, objectiveness and competitiveness” per CAFTA-DR Chapter 9.

Embassy: “For the past two years, the Government of El Salvador has conducted its procurement program in a manner that raises concerns with regard to its government procurement obligations under the CAFTA-DR (Chapter 9 and its associated annexes), which requires an open, transparent, objective and competitive government procurement process that does not prejudge the outcome of a tender.”

In December of 2012, El Salvador approved a procurement order that explicitly excluded non-domestic producers from eligibility for bidding. Passed by executive decree, this particular procurement order had a limited lifespan, and is now no longer valid policy. In January of 2014, the Salvadoran government produced a new call for bids, which provided a much more open bidding process with no exclusions, and even included categorical consideration of seed “importers” under its base for contractor qualifications. The government is currently working with three businesses that import seed from international sources. It’s important to note that these three businesses also participated in past procurement processes, and clearly have not been excluded based on domestic or foreign affiliation.

The timeline (the last two years) that the United States identifies per their concerns is decidedly convenient for the U.S. argument, especially when analyzing the Salvadoran government’s procurement process prior to two years ago. Records from the Ministry of Agriculture in 2009 and 2010 reveal a number of procurement orders for seed, agricultural supplies, and other goods and services (like gasoline for ministry vehicles) that were completed “by invitation” and “direct purchase” methods from a pre-selected business or group of businesses. These methods are the very same purchasing methods that the U.S. currently criticizes El Salvador for on its seed procurement starting 2012.

To our knowledge, the United States did not raise any concerns on agricultural procurement methods prior to 2012.

Embassy: “We are asking the Government of El Salvador to implement the procurement program for corn and bean seeds in a competitive, objective, and transparent manner that demonstrates to all stakeholders both El Salvador’s commitment to the CAFTA-DR, as well as its commitment to good governance. Such principles are inherent in the provisions of the CAFTA-DR.”

Salvadoran small-scale farmers that receive seed through the government distribution program indeed deserve to have access to products procured in an open, competitive, objective, and transparent way. For that reason, it is odd that the United States would criticize the current process that has allowed for product procurement from a more diverse array of businesses that offer cheaper and more competitive prices to the government, and ignore the previous, seemingly less competitive procurement methods. Prior to 2012, just 5 businesses fulfilled the procurement order for corn, compared to 18 currently. These 5 businesses, one of which garnered 70% of the procurement order alone, offered corn at nearly double the price currently offered by largely domestic producers: $350 per 100 pound unit, compared to $124 by current local producers. This price of $124 is also cheaper than what the Government of El Salvador would get on the open commodity market, BOLPROS, which currently offers corn seed at over $130.

Though the United States has yet to define what “competitive” means in practice under CAFTA-DR with seed procurement, more businesses currently offer the government of El Salvador a better product that it prefers at a cheaper price. The fact that the majority of these 18 businesses happen to be local, domestic producers should not be cause for “prejudgement” by the U.S. government and USTR.

Embassy: “[The Millennium Challenge Corporation] MCC is holding the government to its commitments in its action plan, including those related to the procurement program, prior to signing.”

An analysis of Chapter 9 acknowledges that seed procurement can be made by executive decree as long as it is transparent, open, objective and competitive. The Salvadoran government has clearly made substantial progress since 2012–especially when compared to procurement methods utilized prior to 2012. Given the Salvadoran government’s action plan to address a number of other concerns per CAFTA compliance, the United States should stop moving the goal posts on policy reform, and should cease to make an example of domestic growers for the symbolic purpose of pressing a new Salvadoran government on its intent to fulfill an international agreement.

Though USTR holds a seat on the MCC’s Board of Directors, it cannot veto compact approval based on “concerns” per El Salvador’s domestic policies and free trade, especially when no explicit legal action has taken place. Nor is USTR in a position to define for the MCC what “specific progress” means in regard to the Government of El Salvador’s Plan of Action to address, in good faith, free trade concerns. USTR has its own mechanisms for addressing free trade concerns without leveraging other agencies to pressure for things that fall outside of their mandate. Based on the federal legislation that established the Millennium Challenge Corporation, its mandate does not include enforcement mechanisms of free trade compliance. Nor do the MCC’s independent indicators of good governance and trade policy indicate a failure on El Salvador’s part, and therefore do not justify an unprecedented hold up in signing this second compact.